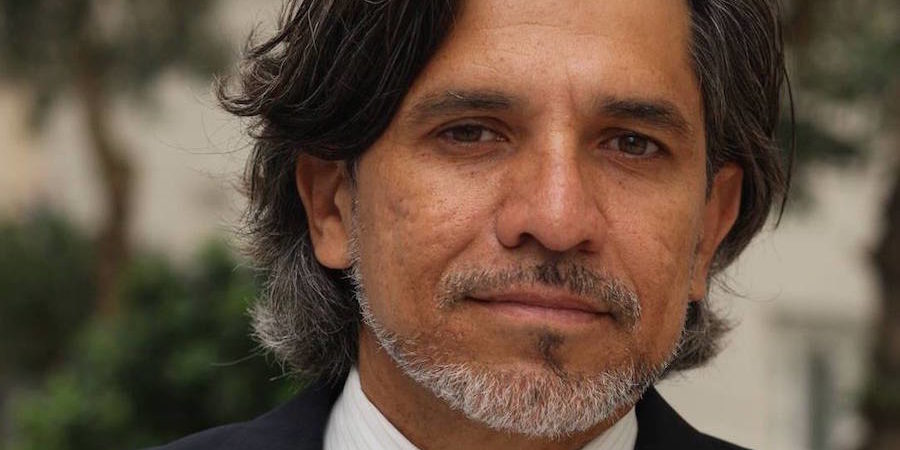

Víctor Madrigal: “States should consider that the valuable contributions of LGBTI people to the construction of the social fabric is one of the ways to guarantee their recognition and inclusion”

In his most recent report, the United Nations Independent Expert on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, Víctor Madrigal, presented an analysis of the ways in which discriminatory laws and social […]

In his most recent report, the United Nations Independent Expert on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, Víctor Madrigal, presented an analysis of the ways in which discriminatory laws and social and cultural norms continue to marginalize and exclude people because of their sexual orientation and / or gender identity in different spheres of society, situations that according to the document, are aggravated when interrelated with other forms of discrimination such as ethnicity, race, socio-economic status, and national origin, among others that lead to definitive states of exclusion and marginalization.

The International Institute on Race, Equality and Human Rights (Race and Equality) spoke with the Independent expert on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity so that, in the light of the reality that Latin American people live, he could present some considerations on the LGBTI situation, the multiple forms of violence they experience today, and present proposals that make it possible to overcome these forms of exclusion.

What is the current situation of LGBTI people in Latin America, how would you characterize it, and what is your interpretation of the current legal situation of LGBTI people in Latin America?

Víctor Madrigal (VM): The problem faced by the human rights of LGBTI people is conditioned, first by a historical framework that has been built over centuries, systems of exclusion and stigma that are based on notions about what the roles that people acquire should be according to their genital configuration. The idea here is to try to understand what these structures are, understand, in addition to what ways in which power is structured in society, and thus understand how the realities of LGBTI people, which are subversive to these systems built over decades and centuries, are violated through frameworks that are intended to defend these power structures.

What the Mandate has done throughout this time, is study the basic causes of stigma and discrimination and come to understand that there are certain structural manifestations: the first is what is known as the “denial” related to the existing idea in some legal systems (or the political message that has been tried to spread), that LGBT people do not really exist in that particular context, justifying their position on the premise that these are ideas imported from some other context.

The second manifestation or mechanism is that of “stigma,” which I have organized into three categories: First, the claim that LGBT existence is criminal in nature, that is, through crime or of criminal legislation. At this moment, there are still 69 countries in the world that criminalize homosexuality, and of these 9 are in the Caribbean Region. Another is the idea that the lives of LGBT people are sinful in nature. Hence the whole structure of the church that is used to create messages of exclusion and discrimination, and the last manifestation or mechanism is the idea of pathologizing, which is connected with the basic idea that LGBTI existence is in some way or another sick or a reflection of pathologies.

The phenomenology of the human rights problems faced by LGBT people is registered in this context and is deeply rooted in patriarchal structure, in social structures that are prevalent in Latin America and that have, as a result, very high levels of social exclusion and violence.

In the report on “Data collection and management as a means to raise awareness about violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity” A / HRC / 41/45 lays out the use of data as part of the strategy of overcoming these contexts and discrimination of violence. Could you explain a little, how is this expressed?

Víctor Madrigal: The context in which I pose this is my conviction that the processes of stigma are based on preconceptions, prejudices, and an exploitation of concerns that the general public have about the very existence of LGBT people, that it is not based on any empirical basis, or in other words, that it is not based on evidence, and therefore, I consider that the strategy to counteract these prejudice structures is through the production of evidence and with this data is essential.

When I started working at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and created the LGBT Rapporteurship, one of the first things we did was create a record of violence, and we realized, for example, that problems of violence against trans women were completely invisible in the data, and therefore in public policy. This is because trans women who were killed, and violently, were usually registered in the police records as men, therefore there was a complete invisibility of their problems from the viewpoint of public policy, but also in regard to social consciousness. The messages were very powerful from every level. The fact that there was no data disaggregated from this population’s point of view, no recognition of the existence of this population at the base of this violence was powerful, but there were also very powerful messages by means of written media that constantly reported murders of trans women as murders of a man dressed as a woman, or a transvestite man, or a man automatically labeled as a sex worker, in short, a number of pre-concepts that didn’t really have any foundation from an empirical base.

So for me, the creation of an evidence base, which allows us to reflect on the true nature of this violence problem, but also the true nature of the social existence of LGBT people, is an essential part of solving the issue.

According to his latest report on socio-cultural and economic inclusion of the population (https://undocs.org/A/74/181), which aspects do you consider the most fundamental for civil society and the States in Latin America?

Víctor Madrigal: On the basis of everything, there is the production of knowledge regarding the reality of LGBTI people’s lives. I insist that obtaining disaggregated data that allows us to understand the situation of LGBT people in relation to education, health, housing, and other sectors highlighted in my report is essential. Without that knowledge base, without that evidence base, it will be absolutely impossible to have public policies that dialogue and impact these lived realities of LGBT people.

Next, it is important that there is a willingness to connect this empirical base with public policy. It is essential to ensure that public policy is informed by this base, but also that when it is being carried out there is a conscious exercise of involving communities, peoples, and populations that are being affected.

Every public policy maker must know in a very clearly the limitations on what we do not know about the realities of these populations. Meanwhile, bringing them into the consultation processes, conducting participatory processes, is the only way to ensure that public policies will have a sustainable impact.

A third element would be related to the fact that in these processes there are very clear political manifestations about the way in which States receive and promote the message of the lives and realities of LGBT people, as long as they consider that they contribute to the social fabric, that they are valuable and worthy of existing in the social fabric, and that the ability and possibility of these people to live free and equal in the context of these societies is a manifestation of their human rights, which are not special rights, which are not unique rights, but it is an essential basis of their human right to be able to live in equality and freedom.

And on the basis of these conditions, I believe that the last element that must be there is the fact that the States recognize that, in these recognitions and in this way of proceeding, there is a fundamental key to ensuring the full potential of LGBT people’s contribution to our society, to enhance and make it possible to unleash and ensure the full potential of the social contribution of these people in our contexts.

Since the exercise of the mandate, you have had the experience of working with various LGBTI activists around the world. What particularities in activism, human rights violations or successful results have you been able to identify in racialized and / or impoverished LGBTI sectors?

Víctor Madrigal: I think that the first achievement to be highlighted is related to the strategic litigation regarding decriminalization. It is extraordinary what has been achieved through judicial activism, for example, in dismantling criminalization systems in India, in the Caribbean itself we have the example of Trinidad and Tobago, we have the example of Belize.

Other achievements that I could mention are related to the access of services and non-discrimination provisions.

I do not participate in the provision of policies for the creation and provision of the Mandate, but I have found it very important how the creation of civil society coalitions has created the mandate and now has gotten an extraordinary renewal through the coalition of more than 1300 civil society organizations that come from 174 countries and have really created a wonderful synergy so that the mandate could be renewed with a fairly forceful majority in the international community. I also believe that networking is a great achievement for the impact on the enforceability of LGBT rights.

If there is any evidence from the last 25 years of experience, it is that social change is possible in our generation. We have gone from contexts of criminalization and pathologizing to contexts of dignity, and I believe that energy of changes, that the change of paradigms is something that can be expected to continue. For the next 25 years, I have the expectation that there will be a world free of criminalization for 2030 and the expectation of a world in which there will be true social inclusion for the next generation.