One year after the signing of the Peace Agreement that ended the Colombian internal armed conflict that had lasted more than 50 years against the FARC-EP guerrillas, an assessment of the progress made toward its implementation has not been favorable for Afro-Colombian communities. The violation of their human rights continues and the legislative and institutional developments that are required for implementing the Agreement are not adequately applying the stipulations of the Ethnic Chapter which is an integral part of the Accords. The post-Agreement conflicts that have been identified in diverse analyses, including what has been produced by the Institute on Race, Equality, and Human Rights,[1] have not been appropriately resolved by the Colombian government. The present article analyzes some of the difficulties and factors that have impeded the conditions that shaped the signing of the Agreement from being strengthened as opportunities for guaranteeing the rights of Afro-Colombian communities.

The signing of the Final Agreement for the Termination of the Conflict and Construction of a Stable and Lasting Peace (hereinafter, the Agreement) on November 24, 2016 was a bittersweet moment for the Afro-Colombian organizations and communities that had undertaken intense advocacy efforts throughout the process of its negotiation. They celebrated the achievement of a process that had opened up opportunities for constructing a sustainable peace through peaceful means, which they had supported from the outset; however, they became concerned about the effects of having been excluded from the process. One exclusion was partially corrected at the last minute through the inclusion of the so-called Ethnic Chapter. This ‘adjustment’ to the final text of the Agreement contains a set of recognitions, principles, safeguards and guarantees, and mechanisms which, if fully applied, would truly lead to the implementation of the Agreement guaranteeing the protection, restoration, and promotion of the ethnic rights that have been acquired and violated. Nonetheless, and given the fact that the rest of the Agreement did not adequately incorporate a differential ethnic-Afro-Colombian focus, the concerns regarding compliance with what was established in the Ethnic Chapter also became a part of this historic moment.

One year after the start of the implementation of the Peace Agreement, these concerns appear to not have been unjustified. In the unfolding of the legislative process, the principal institutional condition for grounding the Agreement, the stipulations of the Ethnic Chapter have not been appropriately incorporated, nor have the prior consent processes been implemented with the communities and organizations. In addition, the progress made in critical actions, such as illicit crop substitution and Development Plans with a Territorial Focus, have not guaranteed the participation of the most affected Afro-Colombian communities. The violence (threats and assassinations of leaders, new displacements, [and] detentions) committed against rural and urban Afro-Colombian communities has not ceased. All of these realities that do appear to be inconsistent with the spirt of the Agreement and have generated disappointment and despair among the communities, represent a threat to the end of the armed conflict contributing to guaranteeing their rights to truth, justice, reparations, and non-repetition.

An analysis of the progress made by the implementation of the Peace Agreement from an Afro-Colombian perspective represents an essential task which the Colombian government must perform so as to correct the inadequate adoption of a differential focus that has prevailed since it was signed. The report[2] produced by the Kroc Institute of International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame [in the] U.S. – the institution designated by the Agreement as the party responsible for performing technical assessments of the implementation – has identified the delay and problems that exist with regard to the provisions of the Ethnic Chapter. According to that report, the Ethnic Chapter is among the subtopics with the lowest levels of implementation. In its recommendations, it identifies some actions that should be adopted so as to overcome this delay. These recommendations and assessment are insufficient for generating the framework of understanding that is required for correcting the direction implementation takes so as to guarantee the adoption of a differential ethnic-Afro-Colombian focus. It is necessary to analyze in greater depth and detail the problems that have presented themselves. To that end, close attention should be paid to the analyses and proposals put forward by Afro-Colombian communities and organizations.

Post-Agreement violence

The persistence of grave violations of the human rights of communities, organizations, and their leaders constitutes the principal problem that must be recognized and addressed. “Peace is costing us our lives” is an affirmation shared by all social sectors committed to defending the stipulations of the Peace Agreement. The assassinations of leaders such as Jair Cortés of Alto Mira y Frontera [Alto Mira and Border] in Tumaco and Bernardo Cuero of the Asociación de Afro-Colombianos Desplazados [Association of Displaced Afro-Colombians] (AFRODES) in Malambo reflect the incapacity and failure of the government to confront a reality that was predicted in various analyses: it was known that the demobilization of the FARC-EP would lead to the elimination of one element of the violence, though would also produce a new armed dynamic due to disputes over territorial control of the zones where it had operated by other illegal armed groups (the ELN guerrillas and paramilitary groups), in connection with drug-trafficking dynamics.

This dynamic, perfectly foreseeable and identifiable in specific territories, should have driven the government to recognize the aggravated risk faced by male and female leaders and consequently, guarantee them appropriate protection measures, which should not be limited to the level of individuals but rather, incorporate measures of collective protection. In many cases, the opposite has transpired. When at-risk male and female Afro-Colombian leaders who have even been victims of threats and attempts on their lives request protective measures, the institutions charged with evaluating their risk assess the situation as being one of ‘ordinary risk.’ The mechanisms for determining the level of risk faced by the leaders of Afro-Colombian communities and organizations requires an in-depth review that truly recognizes the factors of risk associated with the context.

It is precisely from this perspective that an assessment is needed of the factors that are hindering the Colombian government from guaranteeing the right to life and political participation in Afro-Colombian regions such as Tumaco, Bajo Atrato, [and] Río San Juan, among others. The issue in fact goes beyond the militarization of the territories considered by many communities to be inappropriate. In the spirit of the Agreement, they expected and continue to expect the launch of a comprehensive State presence to attend to the communities’ basic needs through a process of prior consent. What has happened, as demonstrated through the massacre of coca-farming campesinos in collective territories of the Alto Mira y Frontera Community Council in Tumaco, is that priority has been given to a vision that conceives of the implementation of the section of the Agreement related to the drug problem from an exclusively ‘criminal’ perspective. As a result, there is no recognition of the impacts of drug-trafficking on the collective life of the communities, or of the conditions necessary for implementing a crop-substitution program.

The ongoing violations of the human rights of Afro-Colombian communities have not been limited to rural territories. Zones in urban contexts of Buenaventura, Quibdó, Bogotá, Cali, [and] Cartagena, among others, where thousands of Afro-Colombians live in a state of forced displacement, also constitute areas disputed by illegal armed groups that coordinate with the dynamics of ‘micro-trafficking’ [of drugs].

Regulatory implementation

The Executive and Legislative Branches’ process of formulating and promulgating laws and decrees for implementing the Agreement has been a priority since it was signed. According to the Kroc Institute report, as of September 2017 44 legislative initiatives had been approved through special mechanisms established for the regulatory implementation of the essential points in the Agreement; another 12 initiatives are underway and should be approved prior to the end of the fast-track’s validity on November 30, 2017. The expectation of Afro-Colombian communities and organizations in terms of this process is the rigorous application of exactly what is stipulated in the Ethnic Chapter. The guarantee of the right to free, prior, and informed consent must be established as the primary tool and principle for ensuring the adoption of a differential ethnic-Afro-Colombian focus. It is in that light that the assessment is very negative.

According to reports from members of the Consejo Nacional de Paz Afrocolombiano [National Afro-Colombian Peace Council] – which as a part of the Comisión Étnica para la Paz y la Defensa de los Derechos Territoriales [Ethnic Commission for Peace and Defense of Territorial Rights] led the process that resulted in the formulation and inclusion of the Ethnic Chapter in the Agreement – there has been virtually no compliance with what was established regarding prior consent and progressivity in said chapter by the Executive Branch and Congress in the regulatory implementation. Neither the Instancia de Alto Nivel con Pueblos Étnicos [High-Level Agency with Ethnic Peoples], defined in the Ethnic Chapter, nor the Espacio Nacional de Consulta Previa de las Comunidades Negras, Afrocolombianas, Raizales y Palenqueras [National Space for Prior Consent for Black, Afro-Colombian, Raizal, and Palenquera Communities] have been appropriately consulted regarding the legislative initiatives approved to date. It does not appear to be feasible for this to be done during the remaining period in which fast-track is in force.

The consequence of this noncompliance has obviously been that said legislative actions lack a differential ethnic-Afro-Colombian focus to prevent regression in the rights acquired and guarantee that the implementation will lead to comprehensive reparations for the violated rights. A profound review is needed of all of these legislative acts with an eye to identifying mechanisms that are necessary for “correcting” the omissions, however in the concrete field of implementation. The problem that will emerge is that in Colombia what is “not named in the laws” is very difficult to demand when those laws are applied. It is true that the Agreement itself, in addition to the Ethnic Chapter, emphasize the commitment to applying differential foci. This should be enough. However, the lack of ethnic-Afro-Colombian specificity in the texts of the legislative acts will make it much more difficult for the institutions that will be charged with applying the laws for implementing the Agreement to adopt said focus.

As an example, the Decree that creates the Commission for Clarification of Truth, Coexistence, and Non-Repetition brings together original texts from the Agreement that mention the impacts of the conflict on the various population groups that are most vulnerable (women, Afro-Colombians, indigenous people, children, etc.). However, when it comes to creating specific mechanisms within the Commission to ensure the application of those differential foci, the Decree only stipulates the creation of a group on gender issues. This specificity in matters of gender is completely adequate and was achieved as a result of the advocacy processes carried out during the process [sic] by women’s organizations. The creation of an analogous group for ethnic matters should be included in this legislative phase, regardless of the advocacy performed by Afro-Colombian organizations. If prior consent had been guaranteed, the Decree probably would have had to include a similar provision as it has for gender issues.

The legislative initiatives related to the Comprehensive Rural Reform have also been monitored and strongly criticized by Afro-Colombian, indigenous, and campesino organizations, and even by a group of Members of Congress. Some pronouncements have put forward strong arguments regarding some legislative acts being inconsistent with what is established by the Agreement. Apparently, mechanisms are being proposed that can turn the clock back in terms of the territorial rights acquired by ethnic communities.

The Framework Implementation Plan (PMI)

The formulation and approval of the PMI has been the other essential institutional process that has transpired during this first year of implementation and is critical for the prospects of guaranteeing the rights of Afro-Colombian communities and those affected by the conflict. According to the Kroc Institute report, “The PMI, and later CONPES, is a key instrument of public policy for translating the Final Agreement into programmatic and budgetary instruments of public policy that integrate the Peace Agreement into the daily and structural functioning of the State.” Said report indicates that this process has been delayed by six months with regard to the timeframe established by the Agreement, which represents a significant obstacle. The inclusion of a differential ethnic-Afro-Colombian focus in the PMI has faced profound difficulties.

The critical component of the PMI for achieving the adoption of a differential focus is the formulation and inclusion of goals and indicators. Any intention established by the Agreement that does not translate into these terms in the PMI will lead it to not being an obligatory commitment for the Colombian government and therefore, will not receive a budgetary allocation.

Representatives of the Ethnic Commission for Peace and Defense of Territorial Rights, which in turn is part of the Special High-Level Agency for Ethnic Peoples, has been actively participating in the spaces created for drafting the PMI. Using their own technical resources, they have drafted and delivered a proposal on technical indicators and goals. However, they have encountered systematic resistance to having their proposals be included. As of this writing, it appears that a version of the PMI will be produced that in fact incorporates the ethnic focus at the level of indicators and goals. Even so, the liaising process between the governmental institutions and Afro-Colombian organizations has evinced a lack of political will and understanding regarding the importance of a differential ethnic focus as a constituent element for the construction of peace.

Strengthening the conditions for effective participation

Since the start of the negotiation process, the Colombian government and FARC-EP coincided in that the victims of the conflict would be at the center. The final text of the Agreement indeed reflects this commitment. Not only in that one of its points is exclusively dedicated to victims’ rights but in fact, all of the Agreement’s points adopt this commitment. As such, the expectation of Afro-Colombian communities was that with the signing of the Agreement, all of the necessary measures would be adopted, from the start of its implementation, in order to guarantee their effective participation. The principle of prior consent stipulated in the Ethnic Chapter reinforced that expectation. Likewise, it appeared that the Special High-Level Agency with Ethnic Peoples that was created would become a fundamental mechanism for safeguarding this participation.

The assessments of the Afro-Colombian communities and organizations regarding the Colombian government’s actions to contribute to strengthening the conditions for their effective participation in the implementation of the Agreement during its first year are unfavorable.

The Special High-Level Agency with Ethnic Peoples was indeed created; however, it has not had the adequate logistical or technical conditions for producing the inputs that are required for participating in legislative processes or institutional design that have been put forward. In addition, in the case of formulating the PMI, the discussion spaces have oftentimes lacked representatives from government institutions with decision-making power. The latter is precisely what has constituted a factor delaying the scope of the Agreement in terms of including essential proposals for guaranteeing the adoption of an ethnic-Afro-Colombian focus.

The effort to strengthen conditions for participation in communities and organizations in the territories (rural and urban) has been even more limited, starting from the absence of systematic educational work that truly permits a minimal understanding of the content of the Agreement and implementation process.

The design of the regulatory and institutional architecture is, without a doubt, an essential requirement for successfully implementing the Agreement. However, organizational strengthening is equally a condition sine qua non for effectively applying the regulations and executing the public policies that can allow the Agreement to become reality. Were said strengthening not to be addressed, we run the risk of maintaining a large gap between what the laws mandate and what is in fact achieved by the public policies that seek to operationalize them.

The assessment of the first year of implementation of the Agreement presented in this article as regards the conditions for guaranteeing the rights of Afro-Colombian communities affected by the conflict is certainly worrisome. The lack of compliance with the stipulations of the Ethnic Chapter is significant. Despite that, there continues to be a margin for the implementation framework to truly become an opportunity for comprehensive reparations and overcoming historic exclusion. Afro-Colombian organizations and communities continue doing their part through a proactive position to contribute to constructing peace. It is the responsibility of the Colombian State and FARC-EP to make a course-correction so as to guarantee effective inclusion in the implementation of the Agreement.

Recommendations

The Institute on Race, Equality, and Human Rights believes that in order to improve the adoption of a differential ethnic-Afro-Colombian focus in the processes of implementing the Peace Agreement, the following recommendations should be addressed:

The Executive Branch of the Colombian government should:

- Ensure the conditions for guaranteeing the right to free, prior, and informed consent in all legislative and administrative acts.

- Increase the resources allocated to the operational and technical functioning of the Special High-Level Agency with Ethnic Peoples.

- Guarantee adequate protective measures for all male and female leaders who are at risk, both in rural as well as urban contexts.

The Congress of the Republic should:

- Guarantee the processes of the right to free, prior, and informed consent in the issuance of legislative acts via the normal route once the fast-track mechanism is no longer in force.

The FARC-EP should:

- Strengthen efforts to ensure its former combatants know and apply the stipulations of the Ethnic Chapter in matters under their purview.

To the international community:

- Cooperation agencies and other donors with a presence in Colombia should prioritize financing the strengthening of organizations at the territorial level from the perspective of [ensuring] effective participation in the mechanisms created for implementing the Agreement.

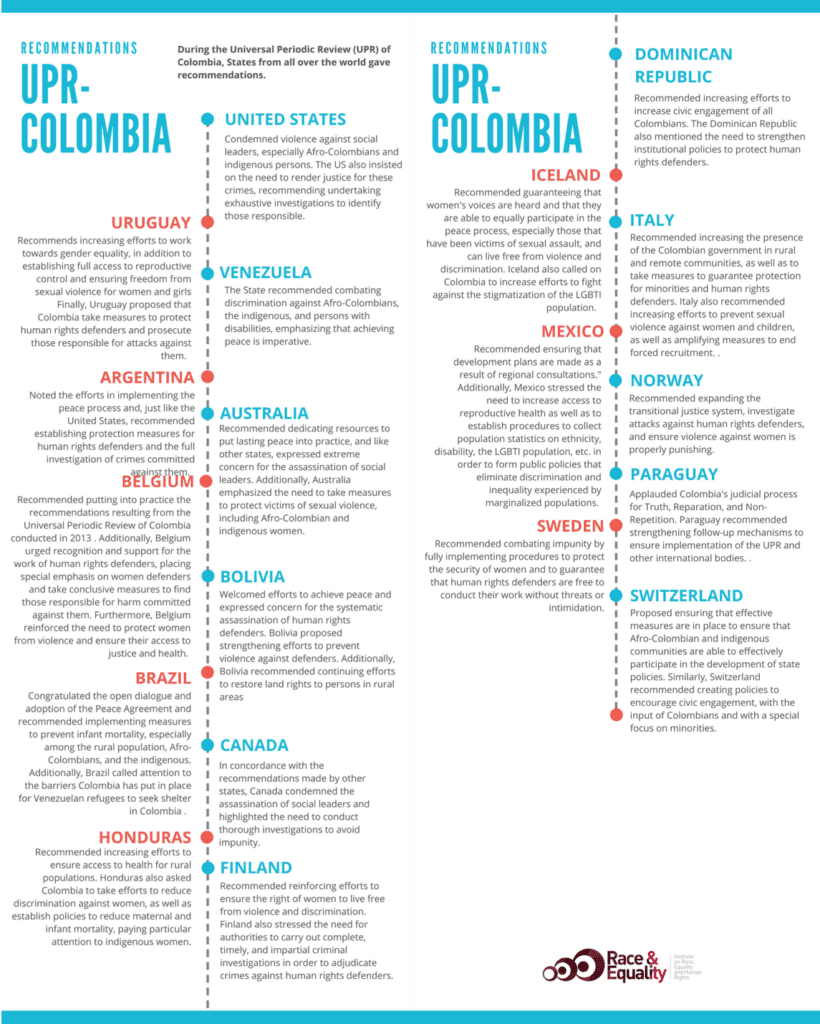

- The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights should perform an on-the-ground visit to the country to specifically assess the situation of Afro-Colombian communities and the state of compliance with the Agreement’s Ethnic Chapter.

To Afro-Colombian organizations and communities:

- Strengthen educational actions aimed at their base focused on the regulations, policies, and programs through which the Agreement is being implemented.

Continue strengthening the use of international human rights protection measures in their processes of monitoring the implementation of the Agreement.

[1] Institute on Race, Equality, and Human Rights. Afro-Colombians and the Post-Agreement: An Analysis of the Conditions for Adopting a Differential Ethnic-Afro-Colombian Focus. Political Analysis Document 1. Colombia office. September 2016. (Available at: http://oldrace.wp/espanol-2/nueva-publicacion-de-instituto-sobre-raza-igualdad-y-derechos-humanos-con-analisis-sobre-el-proceso-de-paz-en-colombia-y-la-situacion-de-los-afrocolombianos/).

[2] Kroc Institute of International Peace Studies. Report on the Effective State of Implementation of the Colombia Peace Agreement. November 2017.