Leaders of Latin America and the Caribbean at the 49th General Assembly of the OAS: “We are facing a grave situation of human rights violations””

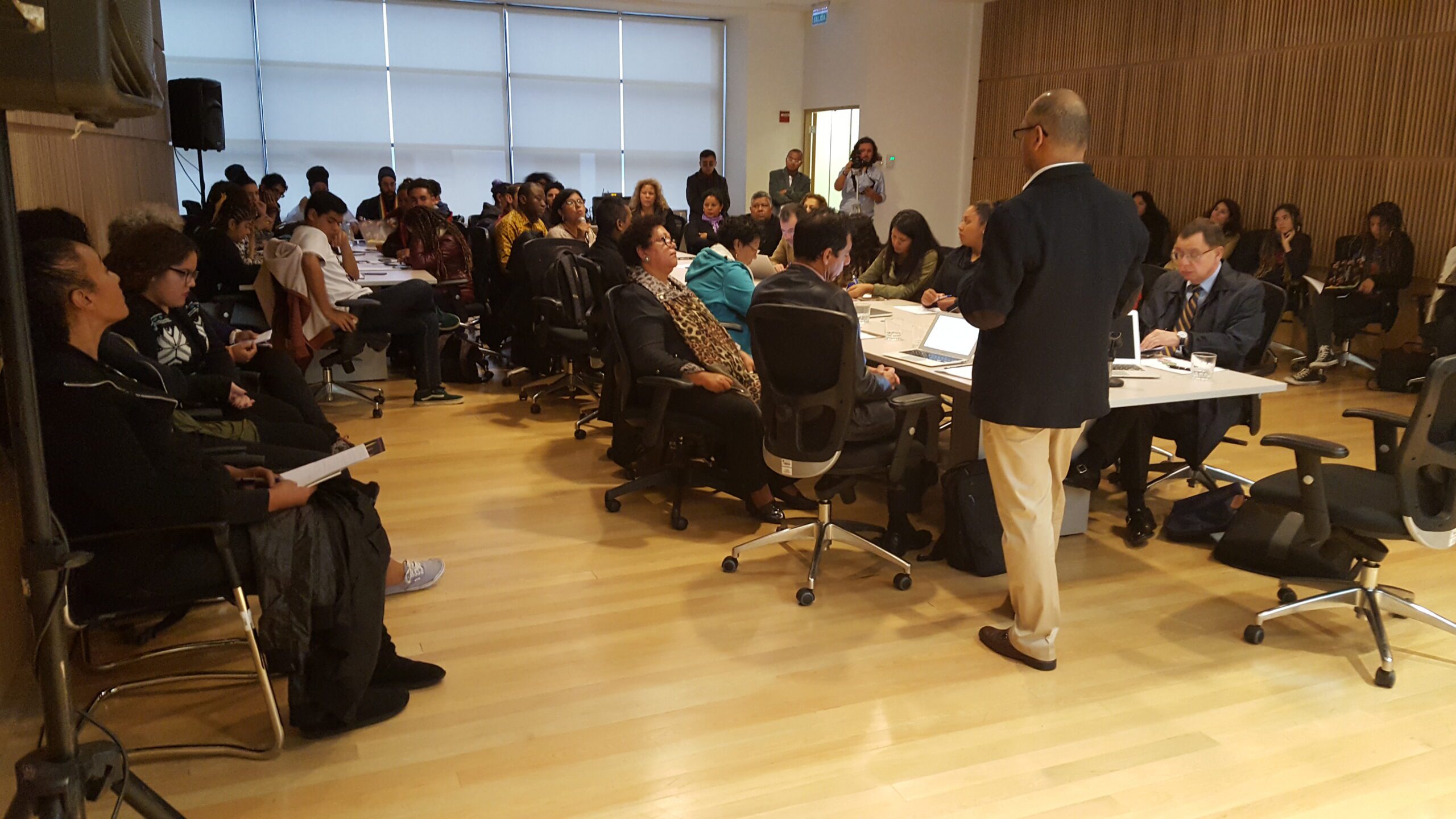

Over the course of the 49th General Assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS), held in Medellín, Colombia from June 25-28, the International Institute on Race, Equality and Human Rights (Race and Equality) held various events, particularly with participation by human rights, Afro-descendent, and LGBTI leaders from Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Paraguay, Brazil, Nicaragua, Mexico, Bolivia, and the Dominican Republic.

These meeting and discussion spaces sought to reflect upon and study the social and political conditions facing human rights in Latin America. These conditions currently have a particular effect upon historically marginalized and invisible populations such as Afro-descendants and LGBTI persons, as do violations of fundamental rights through persecution and harassment by different governments in the region against rights defenders.

We reiterate our condemnation of the absence of Cuban activists who were denied exit from the country by migration authorities, this being a strategy of coercion and repression by the Cuban state to prevent civil society leaders from publicizing the human rights situation on the island.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The Inter-American Form Against Discrimination was held on June 25. Afro-descendant and LGBTI activists from Latin America took part alongside the re-elected Commissioner Margarette May Macaulay, Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons of African Descent and Against Racial Discrimination and Rapporteur on the Rights of Women at the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights.

During their dialogue, activists described the social and political situation with regards to human rights in the region. The president of the Network of Afro-Latina, Afro-Caribbean, and Diaspora Women emphasized the need for women across the region to raise their voices to be heard, speak out, and participate as subjects of human rights. Likewise, the Brazilian activist Rodei Jericó de Géledes expressed the great challenges faced by the Afro-Brazilian population with regards to guarantees and recognition of their rights, especially Afro-Brazilians with diverse expressions of gender and sex, who suffer the highest percentage of homicides worldwide, with Afro-LGBTI people being the most frequent victims.

Rodnei Jerico de @geledes expone sobre los desafíos para la población afro bajo la nueva administración brasileña y @palanquera habla sobre la necesidad de capacitación y formación de mujeres afrodescendientes en las Américas #AsambleaOEA #RazaeIgualdadOEA pic.twitter.com/e6BsBJRkSL

— Race and Equality (@raceandequality) 25 de junio de 2019

In a similar vein, the Colombian LGBTI rights activist and director of Caribe Afirmativo Wilson Castañeda indicated that although the Colombian peace process is unique in the world today by virtue of its reaffirmation of the rights of LGBTI conflict victims, Colombian LGBTI persons continue to be crushed by violence and hate crimes, fueled by hateful public discourses and state indifference to the victims. Castañeda told the audience that “peace is costing us our lives.” This dark side of the Colombian peace process includes the announcement by INDEPAZ that 837 social leaders have been killed, with 17 new alleged cases coming recently.

Commissioner Macaulay shared with the audience the importance of the Inter-American Convention Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, and Related Intolerance, making clear that the Commission has found that Afro-descendants in the Americas suffer from structural discrimination affecting all social rights to which they are entitled.

The representative of the National Conference of Afro-Colombian organizations, Hader Viveros, stated that Afro-descendants continue to be seen as objects rather than subjects, and thus continue to be victims of discrimination and non-recognition of their true needs. María Martínez de Moschta presented evidence to this point, signaling that over 117,000 people remain stateless in the Dominican Republic thanks to state decisions motivated by senseless racism.

Finally, Christian King, director of the organization Trans Siempre Amigas (TRANSA) in the Domincan Republic, and Cecilia Ramírez, director of the Black Peruvian Women’s Development Center (CEDEMUNEP), shared with the participants the importance of being present in international legal bodies such as the OAS General Assembly, highlighting the possibility of using these spaces to bring civil society demands to the fore and to make Latin American social movements’ social and political agendas visible in the struggle for human rights.

Discussion: “The Implementation of the Peace Accords: Social Innovation and Development in Afro-Colombian Territories”

Afro-Colombian leaders held the discussion “The Implementation of the Peace Accords: Social Innovation and Development in Afro-Colombian Territories” on June 25 during the General Assembly. Costa Rican Vice-president Epsy Campbell, Angela Salazar of the Colombian Truth Commission, and Margarette May Macaulay of the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights also participated.

#AsambleaOEA - Comisionada #AngelaSalazar de la @ComisionVerdadC señala que el papel del pueblo afrodescendiente en la implementación del acuerdo de paz en #Colombia sigue siendo muy difícil sin el reconocimiento de las historias, los relatos y las vivencias de los pueblos negros pic.twitter.com/gm6l3hDm5P

— Race and Equality (@raceandequality) 25 de junio de 2019

Leading the discussion, Vice-president Campbell called upon leaders to continue struggling, building, and working for peace despite being faced with Colombia’s “labor pains” as the social and political conflict drags on. Commissioner Salazar stated that the role of the Afro-descendant population in the implementation process is challenged mostly by the lack of recognition for Black history and experiences in Colombia.

The conversation, which centered upon the systematic killing of social leaders, brought up the deaths of over 400 activists according to the national Ombudsman’s office. Recalling the recent case of María del Pilar Hurtado, all those present condemned this trend.

Audes Jiménez, Afro-Colombian leader and representative of the Network of Afro-Latina, Afro-Caribbean, and Diaspora Women, said, “While President Iván Duque is occupied with the immigration of Venezuelans into Colombia and his migration policies, a genocide against social leaders is underway in Colombia, and this must be in he attention of the General Assembly.” She added that in the Caribbean coastal region, killings, attacks, and persecution continue, especially against ethnic groups defending their land and territorial rights.

Francia Márquez, another Afro-Colombian leader, stated that Afro-Colombian people feel abandoned and ignored by the state, allowing Black, indigenous, and campesino communities in the country to be wiped out by violence as they work tirelessly to care for the Earth. “Peace requires us to think of alternative development“. In the name of ‘development,’ we are being killed, threatened, and treated as a military threat,” she said.

It was also clear that structural racism causes women to continue being killed and victimized: “we are furious because we are speaking about peace into an empty discourse, peace has still not arrived to our territories, and we have been the ones suffering deaths,” she added.

Nixón Ortíz, LGBTI activist and director of the Arco Irís Afro-Colombian Foundation of Tumaco, remarked that the lack of commitment from the Colombian state to implement the Peace Accords has led to foci of violence in Afro-descendent territories, which remain unprotected and unattended. “We want to say that we have been resisting with our bodies, songs, and dances. Our weapons are our traditions. But the lack of governance in the territories puts whole populations at risk,” he added.

#AsambleaOEA Nixon Ortíz lider #AfroLGBTI de Tumaco señala que la impletamción del acuerdo de paz en medio de la guerra que se lleva nuestros jóvenes nubla la verdadera paz “Nuestras armas son nuestras tradiciones, son nuestros arrullos, alabaos, que gritan que queremos la paz” pic.twitter.com/tnsrnBH5J1

— Race and Equality (@raceandequality) 25 de junio de 2019

Finally, Father Emigdio Custa Pino, Secretary General of the Nacional Conference of Afro-Colombian Organizations (CNOA), invited the audience to continue struggling, building, and resisting despite the deaths of leaders, to assume the responsibility of those no longer present, both for those present and those who are to come.

Discussion: “Where is Nicaragua Heading? Challenges to Human Rights in the Context of Crisis”

A Nicaraguan delegation traveled to Medellín to participate in the General Assembly and interact with the diplomatic missions in attendance. These civil society members, human rights defenders, and ex-political prisoners participated in the event “Where is Nicaragua Heading? Challenges to Human Rights in the Context of Crisis,” organized by Race and Equality alongside CEJIL.

The opening remarks went to the Vice-president of Costa Rica, Epsy Campbell, while the panel consisted of Marlin Sierra, executive director of the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights (CENIDH), Azahalea Solís, member of the Civic Alliance for Justice and Democracy, Lucía Pineda, head of 100% Noticias news and former political prisoner, Roberto Desogus, Nicaraguan lead for the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and Sofía Macher, member of the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts on Nicaragua.

La estigmatización, criminalización y persecución de defensores ha sido una constante en #Nicaragua, comenta Marlin Sierra del @cenidh, organización de ddhh que fue ilegalmente clausurada y allanada por el Gobierno. "Vivimos bajo la vigilancia, el acoso, la amenaza", agrega. pic.twitter.com/DmkO1vACze

— Race and Equality (@raceandequality) 27 de junio de 2019

During the event, which went on for over two hours, the first three panelists described their experiences defending human rights and working in journalism in the case of Lucía Puneda, while the panelists representing international bodies described the ongoing work of monitoring from outside the country, as well as their commitment to returning once the authorities choose to authorize their missions.

The following day, Lucía Pineda participated in a breakfast with Colombian and international journalists from digital, print, and television outlets. Throughout her stay in Medellín, after having spent almost six months in prison for reporting through 100% Noticias, she was interviewed by various outlets interested in telling her story and making visible the demands of the Nicaraguan people.

The photo exhibition “Put Yourself in My Shoes” launches at the OAS

During the 49th General Assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS), human rights activists from several Latin American countries participated in the premier of a photography exhibition titled “Put Yourself in My Shoes.” The exhibit is the result of a collaboration between Race & Equality and Edgar Armando Plata, M.A. of Universidad del Norte (Colombia).

The exhibit illustrates the work of activists and rights defenders, exploring their fundamental role in defending and advancing human rights. It is on display at the Colombo Americano Institute of Medellín and will be open until August 2019.

Launch of the CIDH Report “Recognition of the Rights of LGBTI Persons” : Afro-LGBTI Perspectives from an Intersectional Lens

At the 49th General Assembly of the OAS, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH) presented its recent report “Recognition of the Rights of LGBTI Persons,” a look at the state of rights for people with diverse sexual and gender expressions. Activists from Brazil, Nicaragua, Peru, and Colombia spoke of the grave situation of vulnerability and violation of fundamental rights that LGBTI persons continue to face throughout the region. The Afro-Peruvian trans woman activist Belén Zapata stated that hate crimes and violence against LGBTI people in Peru are not criminalized, with no laws penalizing these acts despite several documented cases. “We must not continue dying and having our killers out in the streets committing other crimes,” she said regarding the killings of trans people.

Alessandra Ramos de #Transformar denuncia que #Brasil es el primer país de todas las Américas con mayor tasa de asesinatos de personas trans. "Estamos perdiendo mucho de lo que habíamos conseguido" en cuanto a reconocimiento de derechos. pic.twitter.com/OFP9xylWAh

— Race and Equality (@raceandequality) 28 de junio de 2019

The Afro-Brazilian trans leader Alessandra Ramos state that LGBTI people in Brazil are faced with a grave situation of vulnerability and rights violations, particularly because the government of Jair Bolsonaro does not recognize people with diverse sexual orientations or gender experessions. She said that Brazil is the leading country in killings of trans people, with 163 trans victims of hate-crime killings last year. Faced with this situation, she expressed “We exist in order to resist, and we resist in order to continue existing.”

Finally, the Afro-LGBTI Network of Latin American and the Caribbean made a public statement with regards to human rights impacts, violations, and structural discrimination affecting Afro-LGBTI people in the region based upon their sexuality, race, and ethnicity.