Colombian Afro-LGBTI organizations meet with representatives from the JEP

Leaders of Afro-LGBTI organizations from the municipalities of Cauca, Valle del Cauca, Nariño and the Colombian Caribbean explained and denounced the effects and violence Afro-descendants with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities suffered during the armed conflict before representatives of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP).

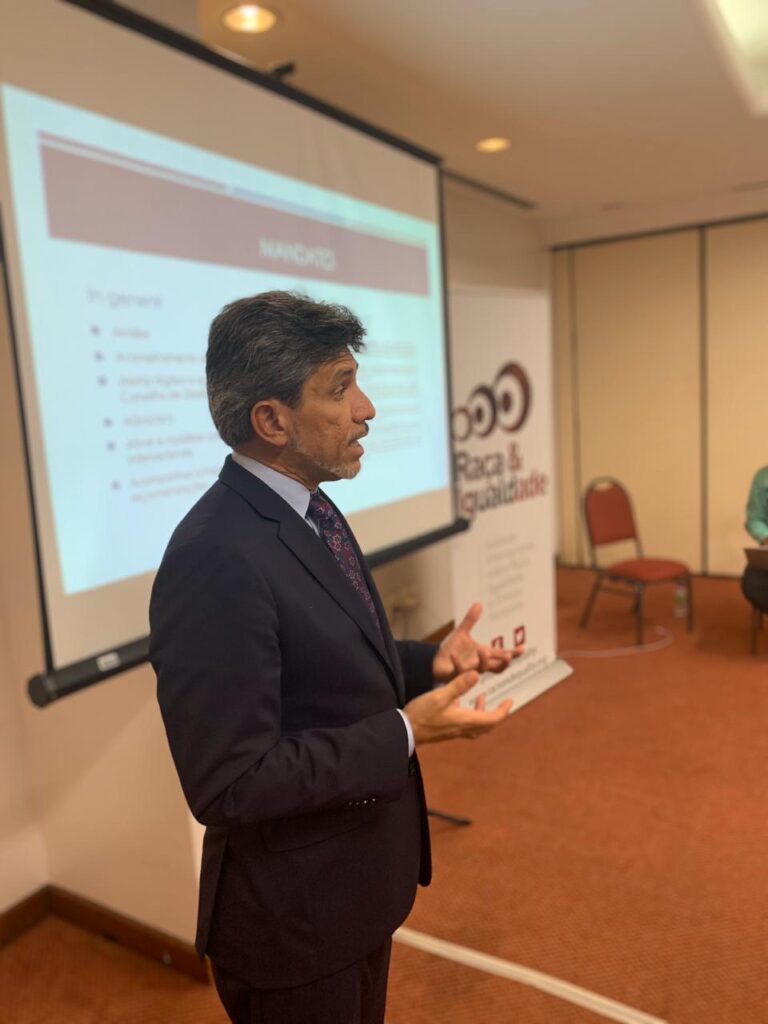

The event that took place on March 12 and 13 is part of a project led by the International Institute on Race, Equality and Human Rights (Race and Equality) with the support of the Canadian government. “The project seeks to make Afro-LGBTI victims of the armed conflict, as well as the causes and differential impacts that these types of violence have on people with diverse sexual identities and expressions, more visible,” said Laura Poveda, lawyer for Race and Equality. In relation to this, Pedro Cortés, Colombian consultant at Race and Equality, highlighted the importance of this meeting as a space that strengthens and increases the participation of Afro-LGBTI civil society organizations before the Comprehensive System of Truth, Justice and Reparation.

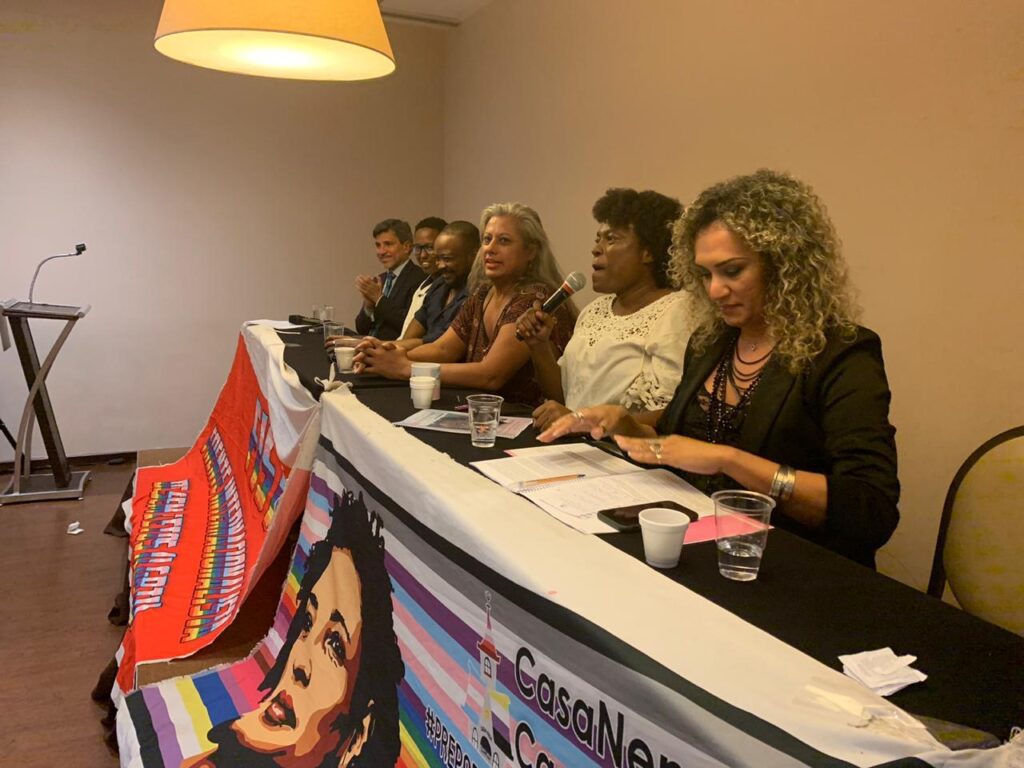

Throughout the meeting, which included the participation of JEP magistrate Heydi Patricia Baldosea Perea, also a member of both the gender and ethnic commissions of the same institution, the participants, through a collective dialogue, delved into the violations and direct effects that Afro-LGBTI groups continue to face in the territories.

Joana Caicedo from the organization Somos Identidad in the city of Cali, pointed out that LGBTI people, especially from the most impoverished communities in the city, which are mostly composed of Afro-Colombians, have faced and continue to face situations of violence by armed actors in the territory. Armed groups during conflicts use strategies to correct of modify expressions that they consider “abnormal”, for example, the most common forms of violence against LGBTI people are forced recruitment and sexual violence.

“LGBTI people are usually forced to hide and try to act normal so as not to be harassed; now, living in different contexts as a black person is difficult, so being LGBTI in contexts of violence and armed conflict further exacerbates the situation,” indicates Caicedo from Somos Identidad.

Vivian Cuello from Caribe Afirmativo emphasized that structural racism still persists in all of society, which is why the armed conflict disproportionately affected Afro-descendant groups. “It is no coincidence that the armed conflict mostly affected a large part of the racialized territories. This is due to an imminent absence of the State in these territories, which allows armed groups to inhabit and take control of the territories,” she added.

According to Angelo Muñoz of the Afro-Colombian Foundation Arco Irís in Tumaco, the “objectification” and “social normalization” of violence against LGBTI people is another one of the main effects diverse groups suffered in the territories where there is and has been armed conflict. He also emphasized the state of violation that represents for the LGBTI groups in Tumaco, not having judicial or social support when it comes to violence against various people.

“In a territory where there is armed conflict, the black and LGBTI are a vulnerable body in an indifferent territory,” added Muñoz.

Judge Baldosea referred to the 7 cases that have so far been opened in the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, thanking and encouraging civil society organizations to present reports that integrate data that may be related to already open cases in order to approach such investigations from an intersectional approach.

Additionally, the Magistrate carefully explained the processes and methods used by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and the way in which these are being reviewed.

“We do not have a clear idea or exact data on how many cases will be opened; to date civil society organizations have submitted an average of 284 reports and the call is open until March 2021. For our part, as body that has a clear mission of clarifying the truth, we will continue working to guarantee a comprehensive process for victims,” said Baldosea.

Likewise, representatives of Afro-LGBTI civil society recommended decentralizing the processes that are being carried out to date in the JEP, to approach communities in the territories through less institutional forms, and thus generate trust and bring the necessary information in the clearest and most concise way.

Through this project, Race and Equality, with the support of the Canadian government, seeks to join the initiatives undertaken by organizations such as Caribe Afirmativo who have already presented documented cases before the JEP of Afro LGBTI victims of the armed conflict in the region of Urabá (northwestern Colombia) and the municipality of Tumaco.